~21m skim, 4,277 words, updated Dec 16, 2025

2022-09-12

A Functional Language for the Erlang BEAM vm.

Programming is tough. Especially at first.

Whatever you are learning or writing, keep in mind that every language was created with a set of principles and use cases in mind - some more than others.

Learn to reject your ego. Learn to love burning code.

Name things what they are. Begin with your program’s final state in mind!

I’ve decided to go all in on Phoenix/Elixir for my next few projects.

See all of my Phoenix notes in the Phoenix Manual.

Elixir is syntactic sugar for Erlang. Elixir actually transpiles to Erlang and runs on Erlang’s BEAM VM. BEAM stands for Bogdan’s Erlang Abstract Machine, or more recently, Björn’s Erlang Abstract Machine, after the maintainers. The BEAM itself is akin to Java’s JVM.

Erlang is a programming language used to build massively scalable soft real-time systems with requirements on high availability. Some of its uses are in telecoms, banking, e-commerce, computer telephony and instant messaging. Erlang’s runtime system has built-in support for concurrency, distribution and fault tolerance. – erlang.org

Phoenix is a web framework that utilizes Elixir and the BEAM to give developers an extremely performant, reliable, stable, and fun to work with web development experience.

Luckily my current employer has excellent learning resources, so I have access to a few courses on Elixir and Phoenix. Focus #1 is to get a solid understanding of Elixir basics: how to write, test, and use the toolbox. The content on this page is largely pulled from these other sources and collected here for reference. Here are the largest sources. Please let me know if you’d like me to take things down for copyright purposes.

Install Elixir.

Follow this install guide.

See Elixir School: Basics – a high-level rundown of the Elixir syntax:

++/2hd and tl functions%{}elixir, exs, or exfor val <- vals do)|>)What’s good about Elixir?

Elixir is functional. An OO approach to a card deck might look like this:

class Card

string suit

string value

class Deck

Card[] cards

f shuffle()

f deal() -> Card

f save() -> Card[]

f load(Card[])An OO approach would dictate that the deck contents are stored in an instance of Deck, and can be manipulated with the class functions.

The functional approach would look like this:

module Cards

f create_deck() -> String[]

f shuffle(String[]) -> String[]

f save(String[]) -> Path

f load(Path) -> String[]There are no classes or instances of classes. The module is a collection of pure functions (methods) and have no internal state.

Mix is the Elixir command line build tool. Useful commands:

mix new <project name> creates a new project.mix test runs unit tests.In Powershell , run:

mix new cards

cd cardsModify lib/cards.ex if wanted:

defmodule Cards do

def hello do

:world

end

endRun interactive Elixir and run the method:

PS C:\Users\Developer\Documents\Elixir\cards> iex.bat -S mix

Interactive Elixir (1.14.0) - press Ctrl+C to exit (type h() ENTER for help)

iex(1)> Cards.hello

:world

iex(2)>Congrats, you have called a method by property in the Cards module.

Note that Elixir implements implicit return of the last value.

Run recompile in interactive Elixir to, er, recompile.

Strings and Lists are simple and recognizable from Python.

["Ace", "Two", "Three"]

"String"Use double quotes.

def shuffle(deck) do

# ...

endFunction and operator names have two components: a name and the arity, for example: ++/2. The compiler will be angered if you attempt to run a function with the incorrect arity.

iex(4)> Cards.shuffle()

** (UndefinedFunctionError)

function Cards.shuffle/0 is undefined or private.

Did you mean:

* shuffle/1We can utilize a method in the standard library - go to the Elixir Docs and searching for shuffle, you’ll find the Enum module.

def shuffle(deck) do

Enum.shuffle(deck)

endEzpz. No import is required as Enum is in the standard library.

iex(4)> recompile

Compiling 1 file (.ex)

:ok

iex(5)> deck = Cards.create_deck

["Ace", "Two", "Three"]

iex(6)> deck

["Ace", "Two", "Three"]

iex(7)> Cards.shuffle(deck)

["Two", "Three", "Ace"]Convention is to use a question mark on a method that returns a true or false value.

Full module up to this point along with run example:

defmodule Cards do

def create_deck do

["Ace", "King", "Two", "Three", "Four"]

end

def shuffle(deck) do

Enum.shuffle(deck)

end

def contains?(deck, card) do

Enum.member?(deck, card)

end

endiex(18)> deck3 = Cards.create_deck |> Cards.shuffle

["King", "Three", "Four", "Two", "Ace"]

iex(19)> Cards.contains?(deck3, "King")

true

iex(20)> Cards.contains?(deck3, "Queen")

falseReusing the Card module from the previous section, we’ll take a look at using list comprehensions to return transformed sets of data.

def create_deck do

suits = ["Clubs", "Diamonds", "Hearts", "Spades"]

for suit <- suits do

suit

end # this actually returns a new array with suits strings.

endiex(26)> Cards.create_deck

["Clubs", "Diamonds", "Hearts", "Spades"]…and it’s not just returning the value of the suits variable.

The wrong way:

for value <- values do

for suit <- suits do

"#{value} of #{suit}"

end

endiex(29)> Cards.create_deck

[

["Ace of Clubs", "Ace of Diamonds", "Ace of Hearts", "Ace of Spades"],

["King of Clubs", "King of Diamonds", "King of Hearts", "King of Spades"],

["Two of Clubs", "Two of Diamonds", "Two of Hearts", "Two of Spades"],

["Three of Clubs", "Three of Diamonds", "Three of Hearts", "Three of Spades"],

["Four of Clubs", "Four of Diamonds", "Four of Hearts", "Four of Spades"]

]Though, this does demonstrate how comprehensions are returned very well, in a nested fashion if run in a nested manner.

We could use List.flatten to resolve this. Still the wrong way.

for value <- values do

for suit <- suits do

"#{value} of #{suit}"

end

end

|> List.flattenor another wrong way

cards = for value <- values do

for suit <- suits do

"#{value} of #{suit}"

end

end

List.flatten(cards)The best solution is to add multiple generators to the comprehension:

for value <- values, suit <- suits do

"#{value} of #{suit}"

endor

for value <- values, suit <- suits, do: "#{value} of #{suit}"Our full (condensed) Cards module now looks like this:

defmodule Cards do

def create_deck do

values = ["Ace", "King", "Two", "Three", "Four"]

suits = ["Clubs", "Diamonds", "Hearts", "Spades"]

for value <- values, suit <- suits, do: "#{value} of #{suit}"

end

def shuffle(deck), do: Enum.shuffle(deck)

def contains?(deck, card), do: Enum.member?(deck, card)

endPattern matching is Elixir’s replacement for variable assignment.

Pattern matching is used anytime you use the equals sign.

def deal(deck, hand_size), do: Enum.split(deck, hand_size)iex(43)> Cards.deal(Cards.create_deck, 5)

{["Ace of Clubs", "Ace of Diamonds", "Ace of Hearts", "Ace of Spades",

"King of Clubs"],

["King of Diamonds", "King of Hearts", "King of Spades", "Two of Clubs",

"Two of Diamonds", "Two of Hearts", "Two of Spades", "Three of Clubs",

"Three of Diamonds", "Three of Hearts", "Three of Spades", "Four of Clubs",

"Four of Diamonds", "Four of Hearts", "Four of Spades"]}Two lists have been returned within a tuple, represented with curly braces. Each position in a returned tuple will have a predictable output.

These can be captured with a line like:

{ hand, rest_of_deck } = Cards.deal(Cards.create_deck, 5)Let’s run that in the interactive console to hammer the point home:

iex(44)> { hand, rest_of_deck } = Cards.deal(Cards.create_deck, 5)

iex(45)> hand

["Ace of Clubs", "Ace of Diamonds", "Ace of Hearts", "Ace of Spades",

"King of Clubs"]

iex(46)> rest_of_deck

["King of Diamonds", "King of Hearts", "King of Spades", "Two of Clubs",

"Two of Diamonds", "Two of Hearts", "Two of Spades", "Three of Clubs",

"Three of Diamonds", "Three of Hearts", "Three of Spades", "Four of Clubs",

"Four of Diamonds", "Four of Hearts", "Four of Spades"]This also works with lists:

iex(47)> arr1 = [ "blergh", 123, :can ]

["blergh", 123, :can]

iex(48)> [ a ] = arr1

** (MatchError) no match of right hand side value: ["blergh", 123, :can]

(stdlib 4.0.1) erl_eval.erl:496: :erl_eval.expr/6

iex:48: (file)

iex(48)> [ a, b, c ] = arr1

["blergh", 123, :can]

iex(49)> a

"blergh"

iex(50)> b

123

iex(51)> c

:canInterestingly, if we put a hard-coded value on the left hand side, Elixir will require the right hand side to have the same value in the right-hand spot.

iex(60)> ["red", color] = ["red", "blue"]

["red", "blue"]

iex(61)> ["redx", color] = ["red", "blue"]

** (MatchError) no match of right hand side value: ["red", "blue"]

(stdlib 4.0.1) erl_eval.erl:496: :erl_eval.expr/6

iex:61: (file)def save(deck, filename) do

binary = :erlang.term_to_binary(deck)

File.write(filename, binary)

endTo load the file, we can do essentially the opposite.

def load(filename) do

{ _ok, binary } = File.read(filename)

:erlang.binary_to_term(binary)

end…and it’s the easiest pickle/unpickle I’ve ever seen. But we should handle the error cases potentially presented in _ok with some pattern matching in the next section.

The load function could be cleaned up like so

to handle all error cases. :error and :ok are atoms (a primitive)

that are commonly used to handle control flow in Elixir programs.

def load(filename) do

{status, binary} = File.read(filename)

case status do

:ok -> :erlang.binary_to_term(binary)

:error -> "File doesn't exist or is corrupted."

end

endThis can be further condensed to:

def load(filename) do

case File.read(filename) do

{:ok, binary} -> :erlang.binary_to_term(binary)

{:error, reason} -> "File doesn't exist or is corrupted. (#{reason})"

end

endThis only makes sense if you remember that Elixir pattern matching both compares and assigns remaining elements. If :ok cannot be matched to the returned result from File.read, the next case is checked.

Warnings about unused variables can be dismissed by placing an underscore before the variable.

{:error, _reason} -> "File doesn't exist or is corrupted."Removing reason entirely will cause the pattern matching to fail with this error:

iex(65)> Cards.load("test")

** (CaseClauseError) no case clause matching: {:error, :eisdir}

(cards 0.1.0) lib/cards.ex:20: Cards.load/1

iex:65: (file)The pipe operator (|>) automatically passes the result of a function as the first argument to the next function. Perfecto!

So something like this:

def create_hand(hand_size) do

deck = create_deck()

shuffled = shuffle(deck)

deal(shuffled, hand_size)

endCan be rewritten to:

def create_hand(hand_size) do

create_deck()

|> shuffle()

|> deal(hand_size)

endGotta love it.

Using

ex_doc

allows developers to export a clean pile of documentation, pulling comments and details from the source code. To install the ex_doc package, add a tuple to your project’s mix.exs file with the following content:

{:ex_doc, "~> 0.29.1"}…and run mix deps.get to install the package.

Module Documentation gives an overview of the entire module and defines a purpose for the child functions.

@moduledoc """

Provides methods for creating and handling a deck of cards.

"""Function Documentation documents the purpose of individual functions.

@doc """

Checks a deck of cards for a unique card.

## Examples

iex> deck = Cards.create_deck()

iex> Cards.contains?(deck, "King of Hearts")

true

"""The above example will generate a section header and code block with syntax highlighted code examples. Six spaces or three tabs are placed before the example code. Unit tests will also automatically run on provided sample code by default.

Run mix docs to generate the documentation for your package.

Tests are a first-class citizen in Elixir, which at this point seems to be batteries-included to a ludicrous degree. I couldn’t be happier with what I am seeing so far.

When the project was created, mix automatically created a cards_text.exs file. Populate it with this simple test.

defmodule CardsTest do

use ExUnit.Case

doctest Cards

test "the truth" do

assert 2 + 2 == 5

end

endPS C:\Users\Developer\Documents\Elixir\cards> mix test

1) test the truth (CardsTest)

test/cards_test.exs:5

Assertion with == failed

code: assert 2 + 2 == 5

left: 4

right: 5

stacktrace:

test/cards_test.exs:6: (test)

Finished in 0.03 seconds (0.00s async, 0.03s sync)

1 test, 1 failureVery nice!

You may have noticed the line doctest Cards - this automatically pulls unit tests from the code examples provided in the documentation we just wrote for our functions in cards.ex.

For example, a doctest for the contains?/2 function:

@doc """

Checks a deck of cards for a unique card.

## Examples

iex> deck = Cards.create_deck()

iex> Cards.contains?(deck, "King of Hearts")

true

"""

def contains?(deck, card), do: Enum.member?(deck, card)A regular unit test asserting that the deck has 20 cards:

test "create_deck makes 20 cards" do

deck_length = Cards.create_deck() |> length

assert deck_length == 20

endThe refute function provides a negative assertion.

test "shuffling a deck randomizes it" do

deck = Cards.create_deck

refute deck == Cards.shuffle(deck)

endHere’s the first sample/learning program we’ve written over the previous few sections.

— cards.ex

defmodule Cards do

@moduledoc """

Provides methods for creating and handling a deck of cards.

"""

@doc """

Creates a list representing a deck of playing cards.

"""

def create_deck do

values = ["Ace", "King", "Two", "Three", "Four"]

suits = ["Clubs", "Diamonds", "Hearts", "Spades"]

for value <- values, suit <- suits, do: "#{value} of #{suit}"

end

def shuffle(deck), do: Enum.shuffle(deck)

@doc """

Checks a deck of cards for a unique card.

## Examples

iex> deck = Cards.create_deck()

iex> Cards.contains?(deck, "King of Hearts")

true

"""

def contains?(deck, card), do: Enum.member?(deck, card)

def deal(deck, hand_size), do: Enum.split(deck, hand_size)

def save(deck, filename) do

binary = :erlang.term_to_binary(deck)

File.write(filename, binary)

end

def load(filename) do

case File.read(filename) do

{:ok, binary} -> :erlang.binary_to_term(binary)

{:error, reason} -> "File doesn't exist or is corrupted. (#{reason})"

end

end

@doc """

Shuffles and deals a `hand_size` of cards

and the remainder of the deck in a second list.

"""

def create_hand(hand_size) do

create_deck()

|> shuffle()

|> deal(hand_size)

end

def create_hand() do

create_hand(5)

end

end— cards_test.exs

defmodule CardsTest do

use ExUnit.Case

doctest Cards

test "create_deck makes 20 cards" do

deck_length = Cards.create_deck() |> length

assert deck_length == 20

end

test "shuffling a deck randomizes it" do

deck = Cards.create_deck

refute deck == Cards.shuffle(deck)

end

endRun example:

iex> Cards.create_hand

{["Four of Clubs", "Two of Diamonds", "Three of Clubs", "Ace of Diamonds",

"King of Spades"],

["Two of Hearts", "Four of Diamonds", "Two of Spades", "King of Diamonds",

"Ace of Hearts", "Two of Clubs", "Ace of Spades", "Three of Spades",

"Four of Spades", "Three of Hearts", "King of Hearts", "Four of Hearts",

"Ace of Clubs", "Three of Diamonds", "King of Clubs"]}Maps store key-value pairs and follow a lot of pattern matching rules.

iex> properties = %{ height: "4ft", weight: "700lbs", hair: "black" }

%{hair: "black", height: "4ft", weight: "700lbs"}

iex> properties.weight

"700lbs"

iex> %{ weight: fatass } = properties

%{hair: "black", height: "4ft", weight: "700lbs"}

iex> fatass

"700lbs"Updating maps is a little more complex then just:

iex(9)> properties.height = "7ft"

** (CompileError) iex:9: cannot invoke remote function

properties.height/0 inside a match

(more error message below this but removing for brevity.)Maps can be updated in two ways:

Map.put(map, key, value) creates a new map with the new value.%{ properties | height: "7ft" } uses head | tail syntax.To add new keys, you can also use Map.put.

A keyword list is a list that consists exclusively of two-element tuples. The first element of these tuples is known as the key, and it must be an atom. The second element, known as the value, can be any term. – elixir docs

iex(12)> colors = [{:primary, "red"}, {:secondary, "green"}]

[primary: "red", secondary: "green"]

iex(13)> colors[:primary]

"red"Keyword lists can also be defined with this syntax.

iex(14)> colors2 = [primary: "yellow", secondary: "magenta"]

[primary: "yellow", secondary: "magenta"]Unlike Python, and like Ruby, lispy Elixir has multiple methods to complete the same task.

Interestingly, duplicate keywords are allowed:

iex(15)> colors3 = [primary: "yellow", secondary: "magenta", primary: "yellow"]

[primary: "yellow", secondary: "magenta", primary: "yellow"]Maps do not allow this:

iex(16)> properties = %{ weight: "200lbs", hair: "black", hair: "blue"}

warning: key :hair will be overridden in map

iex:16

%{hair: "blue", weight: "200lbs"}This interesting property is useful when running database queries with Ecto:

iex> User.find_where([

where: user.age > 10,

where: user.subscribed == true

])If the last argument of a function is a keyword list, the the brackets can be removed. Either just the square ones, or both.

iex> User.find_where where: user.age > 10, where: user.subscribed == true…Elixir still interprets both these syntax configurations as a single key-value list passed to the function.

Start a new Elixir project called identicon:

mix new identicon

cd identicon

mix test

code .Requirements:

The program will look something like:

generate_numbers(username)

|> pick_color

|> build_grid

|> grid_to_imageWe can start this program with these lines. Using built-in libraries, we convert a string to an MD5 hash, then a list of 8-bit numbers.

defmodule Identicon do

def main(input) do

input

|> hash_input

end

@doc """

Converts an input string to a reproducible list of numbers

## Examples

iex> Identicon.hash_input("ryan")

[16, 199, 204, 199, 164, 240, 175, 240, 60, 145, 92, 72, 85, 101, 185, 218]

"""

def hash_input(input) do

:crypto.hash(:md5, input)

|> :binary.bin_to_list

end

endStructs are like maps, with two additional advantages:

In a new file called lib/image.ex create a new module:

defmodule Identicon.Image do

defstruct hex: nil

endThis can be called as %Identicon.Image{}

iex(5)> %Identicon.Image{}

%Identicon.Image{hex: nil}This can be initialized with an entity provided for the hex value, but attempting to add other values like in a map will throw errors.

Modify the hash_input function to return an Image struct:

def hash_input(input) do

hex = :crypto.hash(:md5, input)

|> :binary.bin_to_list

%Identicon.Image{hex: hex}

endiex(7)> Identicon.main("test")

%Identicon.Image{

hex: [9, 143, 107, 205, 70, 33, 211, 115, 202, 222, 78, 131, 38, 39, 180, 246]

}Let’s pull some data out of this struct.

By always using pattern matching we can extract the first few values.

To pattern match you must perfectly describe the incoming entity on the right of the ‘=’ on the left.

def pick_color(input) do

# Pattern match to pull out the hex property.

%Identicon.Image{ hex: hex_list } = input

[r, g, b] = hex_list # <== will throw a big error

# ^^ because the entire pattern on the right is not matched.

[r, g, b | _tail] = hex_list # <== will work correctly

[r, g, b]

endWhich can be further condensed to:

def pick_color(input) do

%Identicon.Image{ hex: [r, g, b | _tail] } = input

[r, g, b]

endUpdate the defstruct line in image.ex:

defstruct hex: nil, color: nilChange the final line in pick_color to:

%Identicon.Image{ image | color: {r, g, b}}Arguments can also be pattern matched.

def pick_color(%Identicon.Image{hex: [r, g, b | _tail]} = image) do

%Identicon.Image{image | color: {r, g, b}}

endEvery method argument can be pattern matched.

iex(16)> Identicon.main("test")

%Identicon.Image{

hex: [9, 143, 107, 205, 70, 33, 211, 115,

202, 222, 78, 131, 38, 39, 180, 246],

color: {9, 143, 107}

}Here’s a brief introduction to how to create and handle “grids” of data.

Remember, we’re passing this hex property which stores a list of numbers to a function that must convert it into a 5x5 grid of numbers mirrored about the y axis. Something like:

1 2 3 2 1

4 5 6 5 4

etc...Code first:

def mirror_row([a, b, c]), do: [a, b, c, b, a]

def build_grid(%Identicon.Image{hex: hex} = image) do

grid =

hex

|> Enum.chunk_every(3)

|> Enum.filter(fn e -> length(e) == 3 end)

|> Enum.map(&mirror_row/1)

# ^^ ick, I don't like syntax that at all, why?

|> List.flatten()

|> Enum.with_index()

%Identicon.Image{image | grid: grid}

endLet’s walk through that transformation line by line.

[209, 107, 225, 173, 190, 129, 143, 34, 222, 175, 46, 227, 48, 79, 233, 179]|> Enum.chunk_every(3)[

[209, 107, 225],

[173, 190, 129],

[143, 34, 222],

[175, 46, 227],

[48, 79, 233],

[179]

]|> Enum.filter(fn e -> length(e) == 3 end)[

[209, 107, 225],

[173, 190, 129],

[143, 34, 222],

[175, 46, 227],

[48, 79, 233]

]mirror_row function to each sublist by passing the function by reference to Enum.map.|> Enum.map(&mirror_row/1)[

[209, 107, 225, 107, 209],

[173, 190, 129, 190, 173],

[143, 34, 222, 34, 143],

[175, 46, 227, 46, 175],

[48, 79, 233, 79, 48]

]|> List.flatten()[209, 107, 225, 107, 209, 173, 190, 129,

190, 173, 143, 34, 222, 34, 143, 175,

46, 227, 46, 175, 48, 79, 233, 79, 48]|> Enum.with_index()[

{209, 0}, {107, 1}, {225, 2}, {107, 3}, {209, 4},

{173, 5}, {190, 6}, {129, 7}, {190, 8}, {173, 9},

{143, 10}, {34, 11}, {222, 12}, {34, 13}, {143, 14},

{175, 15}, {46, 16}, {227, 17}, {46, 18}, {175, 19},

{48, 20}, {79, 21}, {233, 22}, {79, 23}, {48, 24}

]…finally the function returns a new Image struct with the new grid value included.

We could just as easily do some of these steps outside as an overall transformation process on the Image building pipeline, like adding this function as another piped function at the end of main:

def filter_odd_squares(%Identicon.Image{grid: grid} = image) do

filtered_grid =

Enum.filter(grid, fn {a, _b} ->

rem(a, 2) == 0

end)

%Identicon.Image{image | grid: filtered_grid}

endOr as a bit of a claustrophobic one-liner:

def filter_odd_squares(%Identicon.Image{grid: g} = image) do

%Identicon.Image{image | grid: Enum.filter(g, fn {a, _b} -> rem(a, 2) == 0 end)}

endLet’s take the list of “pixels to color” from the previous section and turn it into an actionable set of co-ordinates to paint on a 250x250 pixel grid by providing the top-left and bottom-right points of each 50x50 square.

def build_pixel_map(%Identicon.Image{grid: grid} = image) do

pixel_map =

Enum.map(grid, fn {_value, index} ->

horizontal = rem(index, 5) * 50

vertical = div(index, 5) * 50

top_left = {horizontal, vertical}

bottom_right = {horizontal + 50, vertical + 50}

{top_left, bottom_right}

end)

%Identicon.Image{image | pixel_map: pixel_map}

endThis will add the following data structure to our Image struct:

[

{{0, 0}, {50, 50}},

{{100, 0}, {150, 50}},

{{200, 0}, {250, 50}},

{{50, 50}, {100, 100}},

{{100, 50}, {150, 100}},

{{150, 50}, {200, 100}},

{{50, 100}, {100, 150}},

{{100, 100}, {150, 150}},

{{150, 100}, {200, 150}},

{{50, 150}, {100, 200}},

{{100, 150}, {150, 200}},

{{150, 150}, {200, 200}}

]Documentation can be found at erlang.org/docs/18/man/egd

First, we must ‘download and install the library’ in two steps:

{:egd, github: "erlang/egd"} # 1. add this to your depsmix deps.get to download the new dependency. The latest compatible version should be automatically fetched.By adding the following two functions to our image processing pipeline, we write the generated coordinates to an image file!

def draw_image(%Identicon.Image{color: color, pixel_map: pixel_map}) do

image = :egd.create(250, 250)

fill = :egd.color(color)

Enum.each(pixel_map, fn {start, stop} ->

:egd.filledRectangle(image, start, stop, fill)

end)

:egd.render(image)

end

def save_image(image, filename) do

File.write("#{filename}.png", image)

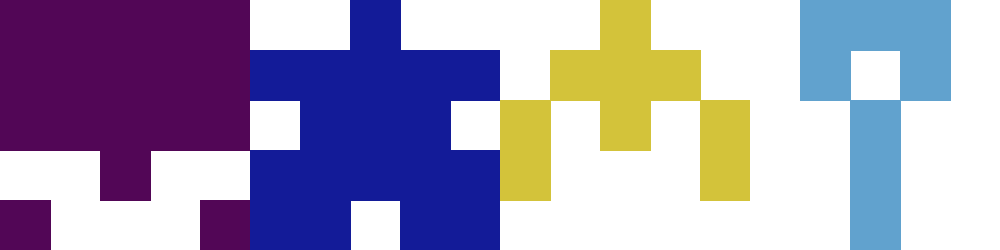

endHere are four examples of generated Identicons:

The next section lists the full sample code.

— identicon.ex

defmodule Identicon do

def main(input) do

input

|> hash_input

|> pick_color

|> build_grid

|> filter_odd_squares

|> build_pixel_map

|> draw_image

|> save_image(input)

end

def save_image(image, filename) do

File.write("#{filename}.png", image)

end

def draw_image(%Identicon.Image{color: color, pixel_map: pixel_map}) do

image = :egd.create(250, 250)

fill = :egd.color(color)

Enum.each(pixel_map, fn {start, stop} ->

:egd.filledRectangle(image, start, stop, fill)

end)

:egd.render(image)

end

def build_pixel_map(%Identicon.Image{grid: grid} = image) do

pixel_map =

Enum.map(grid, fn {_value, index} ->

horizontal = rem(index, 5) * 50

vertical = div(index, 5) * 50

top_left = {horizontal, vertical}

bottom_right = {horizontal + 50, vertical + 50}

{top_left, bottom_right}

end)

%Identicon.Image{image | pixel_map: pixel_map}

end

def hash_input(input) do

hex =

:crypto.hash(:md5, input)

|> :binary.bin_to_list()

%Identicon.Image{hex: hex}

end

def pick_color(%Identicon.Image{hex: [r, g, b | _tail]} = image) do

%Identicon.Image{image | color: {r, g, b}}

end

def build_grid(%Identicon.Image{hex: hex} = image) do

grid =

hex

|> Enum.chunk_every(3)

|> Enum.filter(fn e -> length(e) == 3 end)

|> Enum.map(&mirror_row/1)

# ^^ ick, I don't like syntax that at all, why?

|> List.flatten()

|> Enum.with_index()

%Identicon.Image{image | grid: grid}

end

def filter_odd_squares(%Identicon.Image{grid: g} = image) do

%Identicon.Image{

image

| grid:

Enum.filter(g, fn {a, _b} ->

rem(a, 2) == 0

end)

}

end

def mirror_row([a, b, c]), do: [a, b, c, b, a]

end— image.ex

defmodule Identicon.Image do

defstruct hex: nil, color: nil, grid: nil, pixel_map: nil

endThe most major Elixir topic has its own manual in the tools section, as originally it took up far more than half of this webpage and certainly deserved its own ’tools’ page:

See all of my Phoenix notes in the Phoenix Manual.

Pages are organized by last modified.

Title: Elixir

Word Count: 4277 words

Reading Time: 21 minutes

Permalink:

→

https://manuals.ryanfleck.ca/elixir/